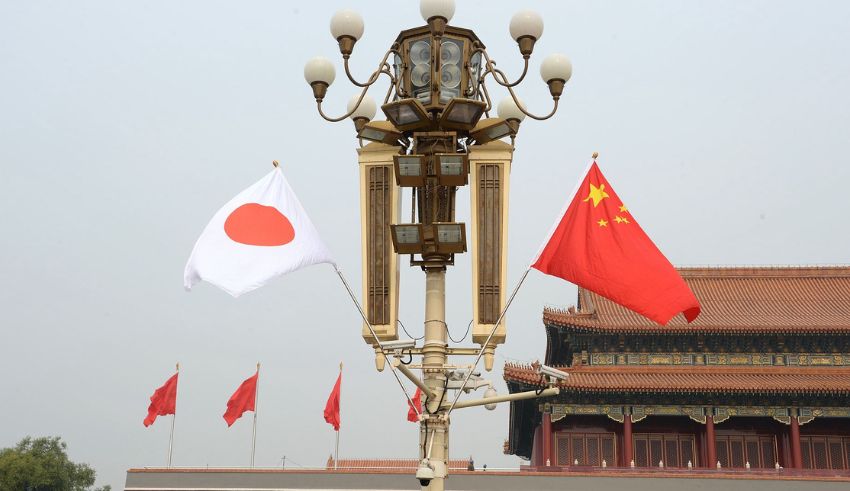

Amid China’s deepening property crisis, economists are sounding alarms about the potential parallels with Japan’s lost decades. The specter of economic development “turning Japanese” looms large as China slid back into deflation in October, raising concerns about its economic trajectory for 2024 and beyond. The complexity of addressing this challenge is exacerbated by Beijing’s perception that time is on its side, despite global investors increasingly withdrawing capital from Chinese assets. This shift has prompted economists to extend timelines for China’s potential GDP surpassing the United States.

Observers note that investors historically haven’t profited significantly from betting against China, as the Communist Party effectively managed crises over the past three decades. However, with China facing headwinds and the economic outlook dimming, analysts argue that the leadership must prioritize key lessons from Japan’s experience after its bad-loan crisis.

Lessons from Japan’s Lost Decades

Beijing finds itself potentially behind the curve as global headwinds gather momentum. Critics argue that China’s leaders have been cautious in implementing fiscal and monetary stimulus, a stance influenced by President Xi Jinping‘s emphasis on deleveraging in both the property sector and among debt-burdened local governments. The perceived tardiness in responding to economic challenges has contributed to the narrative that Xi’s administration is underestimating the impact on growth, further fueling capital flight.

Keep Reading

The historical lesson from Japan is clear: Tokyo’s slow response to its bubble economy’s implosion allowed deflationary forces to take root. Once Japan belatedly ramped up stimulus, the deeply ingrained deflationary trends proved challenging to reverse. To avoid a similar fate, China must act decisively and on a large scale.

China’s property crisis demands a robust policy-driven reform approach to cleanse developers’ balance sheets of questionable assets. The centrality of the property sector, contributing up to 30% of GDP, underscores the urgency and stakes involved. Citigroup economists estimate that China’s property market surpassed $65 trillion in 2020, exceeding 3.6 times the country’s annual GDP and surpassing the combined property sectors of the US, EU, and Japan.

A key risk for China lies in prolonging the process of purging developers of toxic assets, as this could deepen the deflationary trajectory. The government needs to address the root issues in the property sector to create a sustainable foundation for economic recovery.

The cautionary tale of Japan’s lost decades serves as a crucial guide for China. Japan’s sluggishness in comprehending the impending economic pain and the belated nature of its responses underscore the importance of proactive and timely policy measures. While the specifics of each country’s situation differ, the overarching theme is the need for China to learn from Japan’s mistakes and tailor its responses to the unique challenges it faces.

As global investors show a growing inclination to withdraw capital from Chinese assets, China’s leadership must navigate the complex terrain of economic challenges and external pressures. The perceived lack of urgency in addressing economic concerns has further fueled concerns about China’s ability to weather the storm.

In conclusion, as China grapples with its property crisis, the specter of “turning Japanese” in terms of economic development looms large. To avert a potential lost decade, Beijing must heed the lessons from Japan’s experience, acting swiftly, addressing root issues in the property sector, and learning from historical mistakes. The global economic landscape is shifting, and China’s ability to adapt and implement effective policies will be crucial in determining its trajectory in the coming years.